Foreign Policy, August 19, 2011

Foreign Policy, August 19, 2011

The media has been quick to depict the Israeli tent protests as a middle class movement. But there are other groups taking part: Palestinians, low-income Jewish Israelis, migrant workers, and African refugees. While all of these groups face a number of serious problems—as does Israel’s middle class—one was living outdoors in Tel Aviv long before the first protest tent was pitched.

Talk a walk through south Tel Aviv’s Levinsky Park on any day of the year and you’ll see dozens of African refugees sleeping on the grass. But they’re not here in protest. These men and teenage boys are homeless.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu calls them “infiltrators.” The state, however, has reported to the U.N. that about 90 percent of Israel’s approximately 30,000 asylum seekers are indeed refugees. Most come from Eritrea—a country gripped by a brutal dictatorship, fraught with religious persecution—and war-torn Sudan. Some have escaped genocide in Darfur. Many flee first to Egypt, where they might spend several months or years working. From there, they walk to Israel, making making a treacherous journey through the Sinai. A significant number of the refugees are “unaccompanied minors”—teenagers who made this trip alone.

Since Israel’s founding in 1948, the country has given status to about 200 refugees, mostly Vietnamese boat people and Christian Ethiopians. The recent wave of asylum seekers—which began with a trickle in the early 2000s and gained momentum around 2006—has been subject to what Amnesty International calls a “policy of non-policy.” While international law forbids Israel from deporting the refugees, the state refuses to grant status or work visas to a tremendous majority.

But the refugees have to work, of course. So they are forced to enter the black market. There, they often contend with wages that fall far short of the legally-mandated minimum. Sometimes they face “employers” who “hire” and then refuse to pay.

All this leads to tremendous difficulties finding affordable housing.

Their wages too low, rent too high—and receiving no help from the government—refugees are left with few options. In a bid to bring the cost of living down, they cram themselves into apartments, sometimes as many as a dozen to a room. Or they sleep in public places, like south Tel Aviv’s Levinsky Park.

As the number and visibility of refugees has grown, the issue has become increasingly contentious. In July of 2009, the Oz Unit—the strong arm of the Interior Ministry’s Population and Immigration Authority—began enforcing the hitherto ignored Gedera-Hadera policy, which forbids asylum seekers from living in the center of the country.

In the summer of 2010, 25 Tel Aviv rabbis signed an edict that forbids Jewish Israelis from renting apartments to “infiltrators.” A small group of real estate agents in south Tel Aviv—where most of the city’s asylum seekers live—answered the call and began turning away African refugees.

Last year also saw the government announce its plans to build a detention center for African refugees. The barebones facility, which will house women, men, and children, will be located in the desert. It will be cramped and without air-conditioning. Speaking to the Israeli daily Yediot Ahronot, an anonymous government official explained, “The instruction is to avoid indulging them, so this does not become a recreational facility.”

But many Jewish Israelis and local NGOs are in the other proverbial tent. In the summer of 2009, a public outcry put an unofficial end to Gedera-Hadera. On one occasion, the Oz Unit filled a bus with African refugees, with the intent of sending them out of Tel Aviv. By forming a human chain around the vehicle, Jewish Israelis stopped the expulsion.

In December of 2010, Jewish Israelis and African refugees took to the streets of Tel Aviv to demonstrate against the detention center, marching 1000-strong. While the number seems small in comparison to today’s tent protests, it was large enough to attract the local media’s attention.

Concerned citizens have started everything from grassroots initiatives to help feed the refugees to full-fledged organizations like ASSAF (Aid Organization for Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Israel). The African Refugee Development Center, which was founded by a Christian Ethiopian who received legal status in Israel, relies heavily on volunteers—Jewish Israelis who are there in the spirit of tikun olam, repairing the world. And every spring since 2008, individuals and NGOs have come together to hold a Passover seder for Tel Aviv’s asylum seekers. Together, they celebrate the ancient Hebrews’ flight from oppression in Egypt. It is not lost on anyone that the biblical story of exodus bears uncanny similarities to that of the African refugees.

The refugees’ presence at the seder, and in Israel, strikes at the heart of what it means to be a Jewish state. Is it about demographics alone? Or is it about values, like the biblical command to care for the strangers among us? Can Jewish Israelis preserve both their hegemony and their humanity?

What’s really at issue here is the national identity—or who gets a seat at the table.

The tent movement opens up other sides of the same issue by demanding that the state give the collective a bigger slice of the pie. But implicit in the idea of distribution is the question: who?

Who is part of the collective? All citizens? All Jewish Israelis? Or just Jewish Israelis those who live inside the Green Line? And what about all the “others”, the non-Jews who live inside the 1967 borders: Palestinian citizens, migrant workers, and African refugees?

Shouldn’t the government give those who live inside the Green Line the same benefits as or more than those who live, at great expense, beyond it? Or does the government only care to help those Jewish Israelis who push an expansionist agenda? Is Israel about land alone?

And what about Palestinian residents of the West Bank, who live under de facto annexation? What piece of the pie do they get? Where’s their seat and at what table?

Until the Israeli collective—and that includes the tent movement—tackles these pressing questions of identity, until borders are set and the state figures out what this project called Israel is and who it includes, both the refugee and housing crises will remain unresolved.

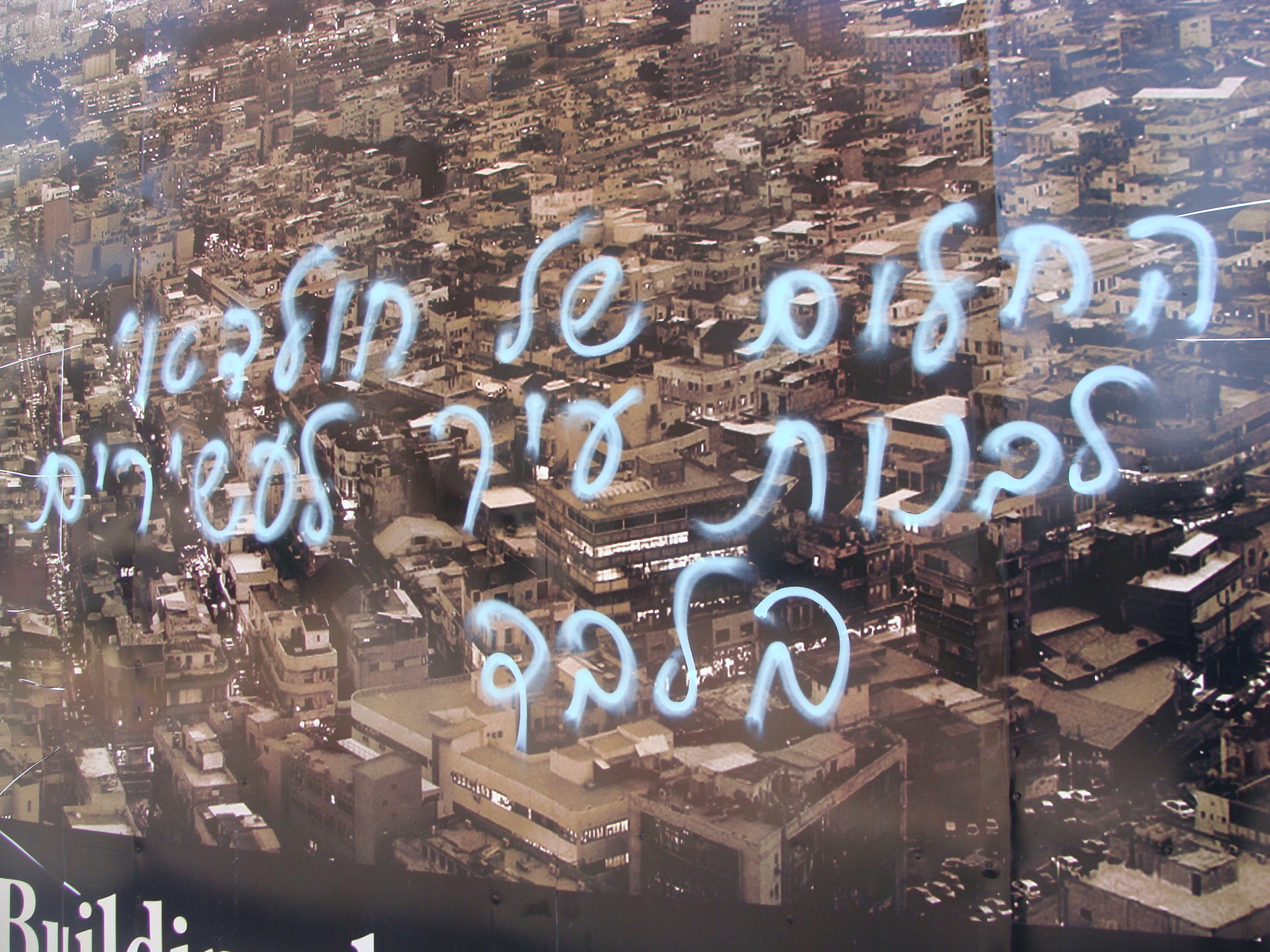

Photo: Mya Guarnieri. The writing was on the wall months before the tent protests began. This picture, taken in April, shows graffiti that reads: “The dream of [Tel Aviv mayor] Huldai is to build a city for the rich alone.” Where would African refugees fit into that capitalist vision?