The Caravan, February 1, 2012

When I put my silver digital recorder on the table, Kidane Isaac, an Eritrean refugee, eyes it and shifts in his chair. He angles his broken straw fedora downwards, tipping the rim lower, as though to cover his face.

The hat, which has a black band and a hole in the top—bits of straw unravelling, sticking this way and that—doesn’t suit the red, white and blue windbreaker Isaac wears. It’s also a poor choice for the weather. It’s a wintry day in Israel and the stylish summer hat is ineffective against the cold.

Not to mention that the fedora seems out of place here, at a coffee kiosk in South Tel Aviv’s Central Bus Station. The surrounding neighbourhoods, the poorest in the city, are home to a large population of foreign workers and African refugees as well as a handful of Palestinian collaborators. While some migrant labourers make enough to send remittances home to their families, most African refugees are barely hanging on to the bottom rung of the socioeconomic ladder. Some have fallen off completely—homeless, they live in the parks near the Central Bus Station.

When he opens up to me later—sliding his fedora back on his head, leaning forward, putting his elbows on the table—I’ll learn that Isaac, 25, isn’t homeless. But he is unemployed. Too proud to use the word, he says, “I’m taking a break.”

Jobs are scarce for Israel’s roughly 35,000 African refugees. The state does not provide work visas for them so they are forced to enter the black market, where they face exploitation. Because of increasing racism, refugees sometimes have a hard time finding work. Even if they can scrape together the money to rent an apartment, some Jewish landlords refuse to rent to foreigners.

Nor does Israel process their requests for asylum—a “policy of non-policy” that has been sharply criticised by human rights organisations, including Amnesty International. But, because Israel does not deport Sudanese and Eritreans to their home countries—as it does undocumented migrant workers—it tacitly admits that they are refugees.

Isaac left Eritrea five years ago, he explains, because his mandatory military service consisted of construction work, a situation he likens to “forced labour”.

“They don’t pay you, you don’t get to see your family,” Isaac, one of nine children, says. “I felt like I wasn’t a citizen in my own country, you know what I mean?”

According to the United States Department of State, military duty in Eritrea is “effectively open-ended” and human rights violations run the gamut from abuse and torture of prisoners and army defectors to “arbitrary arrest and detention” to “unlawful killings by security forces”. Civil rights are severely restricted, as is freedom of movement.

So in 2007, Isaac left. He fled to Sudan, where he lived in a refugee camp close to the Eritrean border. Because the security cooperation between the two countries made Isaac feel unsafe, he moved on to Libya where he spent more than three years “living in the hands of the smugglers”.

While he tried several times to cross the Mediterranean and reach Italy, Isaac recalls, he was passed from smuggler to smuggler. It’s the typical experience of African refugees in Libya, he explains, nonchalantly. “Or you might get put in jail and then you pay a lot [to get out]. There’s a lot of bribery and corruption in Libya.”

In 2010, he abandoned any hope of reaching Europe and, because he understood Israel to be the “only democracy in the Middle East”, he set his sights on Tel Aviv.

He adds, however, that when he left Eritrea, he had “no intention or inclination to go to Israel. At all, at all”.

He’d heard about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, “all the problems and the Israeli Army. After what I’ve been through in Eritrea,” he says, throwing up his hands, “Khallas,” Arabic for enough.

“I wanted a place I could go and live peacefully,” he adds. “That’s why I preferred to spend all those years in Libya, trying to reach Europe.”

Isaac says he has been shocked by the conditions African refugees face here. “It doesn’t have any proper policy for us. [Refugees] are not allowed to do anything. I would say it would be better for [us] in prison.”

Jail, he explains, would be more honest than the current situation, which he calls a “trick”.

“Because then [the Israeli government] can say, ‘Oh, you’re free and you’re working and you’re living and, okay, we have African migrant workers here.’”

I think of the detention facility the state is building in the south of Israel to house African refugees caught entering the country. I consider the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who were dispossessed when Israel landed upon them. I think of the Israeli blockade of Gaza, the occupation of the West Bank and the Golan Heights. Checkpoints. Home demolitions. Political prisoners.

I think of what the Jews have themselves suffered and the biblical command to care for the strangers among us.

“Do you believe in God?” I ask Isaac.

Isaac angles his hat, which I have come to see as a small act of rebellion to circumstance. “Yes, I do,” he answers.

“Even after all this?”

“Religion, I don’t believe in religion. It’s just a drop, some sort of organisation … But I believe in some superpower or whatever.”

Since the state of Israel was established in 1948, it has granted recognised status to fewer than 200 refugees.

Instead of reviewing the cases of African asylum seekers, the Israeli government calls them a faceless mass, “infiltrators”. It’s a word preferred by politicians, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who also claims that Africans are a “threat” to the “character of the country”, our “Jewish and democratic” state.

On 9 January, just a week after I interviewed Isaac, the Israeli Knesset passed a parliamentary bill that modifies the 1954 Prevention of Infiltration Law. Initially created to keep Palestinians from returning to their homes in Israel after the 1948 war, the updated legislation will subject African refugees and their children to three years in jail, without trial. Those from “enemy countries”, including the Darfur region of Sudan, could be imprisoned indefinitely.

But, even before this legislative change, Africans caught entering Israel via its porous southern border with Egypt already faced jail time. Sunday Dieng, a 26-year-old refugee from what is now South Sudan, was held in an Israeli prison for 14 months in 2006 and 2007.

When I ask about the conditions and whether or not he received adequate food, Dieng looks down at the coffee I’ve bought him and gives a polite smile. The gesture matches his slightly formal dress. He wears a starched shirt with a stiff collar. His brown sweater is zipped up. A tiny Mercedes pendant hangs from the tab.

“Yeah, food was no problem,” he says, still looking at his cup. “But, you know, to live in jail for one year and two months for no reason, even though you have food and everything—it’s terrible. It’s very difficult.”

He looks up at me and flashes his teeth to make me, or himself, feel better, perhaps.

“It causes damage to the [mind], because you know you didn’t do anything wrong, you didn’t do any crime.” Dieng, who was not charged with a crime, was held without trial.

He forces another smile before he goes back to the beginning, to 1993.

Dieng was 12 when his village was bombed and soldiers from northern Sudan killed his parents, before his eyes. He and his eldest brother fled, eventually making their way to Ethiopia. But Dieng had his heart set on studying. The refugee camps lacked “proper facilities”, he says, so he went on to Egypt alone.

Because he didn’t feel safe there, he eventually continued on to Israel, making his way through the Sinai on foot until he reached the border.

Speaking of Israel’s unwillingness to process requests for asylum and the refugees’ inability to support themselves financially, Dieng remarks, “How can you let someone into your house if you don’t want to give him food, if you don’t want to give him a place to sleep? This is like killing him in a political way.”

With contributions from Yohannes Lemma Bayu, founder and director of the African Refugee Development Center.

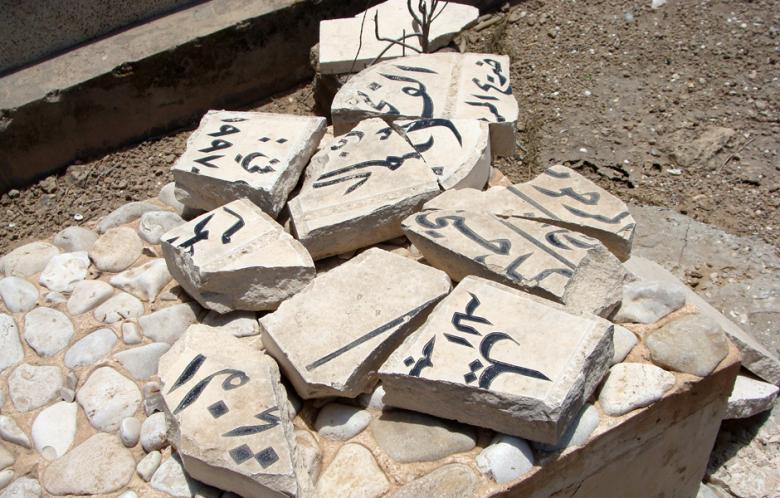

Photo: Mya Guarnieri. Refugees march in Tel Aviv in December of 2010. The sign reads: “We asked for shelter, we received jail.”