Tablet, June 19, 2012

I’m used to seeing abbreviations on Twitter, Gchat, and SMS. But I was surprised recently when an editor closed an email with “Rgds.”

The “s” on the end helped me guess that it wasn’t short for “Rigid” or “Raged,” or so I hoped. Given the context, I assumed he meant “Regards.”

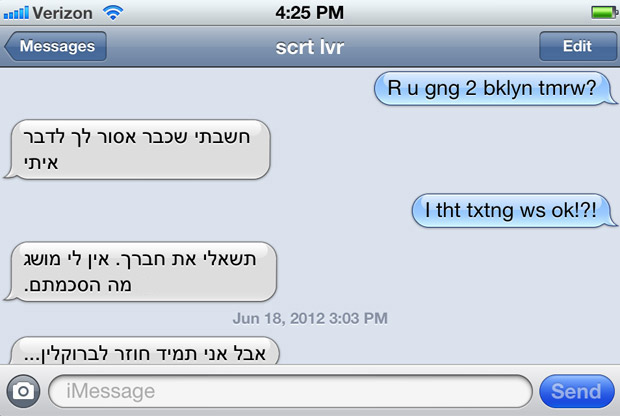

But I wondered how such a word ended up in a business letter? Did it mean that Twitter-ese is making its way into formal, written correspondence? And “Rgds”—a string of consonants, vowels inferred—reminded me a bit of Hebrew. While a dot system helps Israeli children learn vowels, the dots eventually come off, like training wheels, and adults read and write without them.

Might Twitter and SMS push vowels out of English? Could the language end up looking more Semitic than Germanic?

While text messages limit users to 160 or 320 characters, according to Dr. Naomi Baron, a linguistics professor at American University and the author of Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World, the average SMS spans only 20 to 40 characters. So brevity isn’t forced upon us, it’s more a matter of “how much we want to type.”

And typing has gotten easier with the iPhone and other devices that have full keypads; auto complete helps, too.

Abbreviations are a way “to show that you’re hip, you’re in the know, you’re cool,” Baron says. They’re not necessary. Nor are they new. They’ve been popular for at least 1000 years.

“There were abbreviations…out the wazoo,” Baron explains. “Because if you’re writing on parchment and you’re copying manuscripts [by hand], you would like to save sheep hides and you’d like to save your efforts.”

The advent of the printing press didn’t change this. Instead it standardized some abbreviations. Still people—out of either laziness or ingenuity, whichever you prefer—kept shortening words. As is the case today, vowels were often the thing to go.

Baron offers an example from the eighteenth century, when gentlemen closed written correspondence with “Yr hm srv,” short for “Your humble servant.”

Acronyms have also been trendy throughout history. In the 1930s and 1940s, Baron says, friends signed letters with B.F.F.—best friends forever.

I’m surprised to hear this. I remember B.F.F. from my pre-teen days, in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was everywhere: on the notes we passed in class; in the saccharin sentences we scribbled into each other’s notebooks; on the heart-shaped pendants that best friends wore.

Was it really 60 years old?

“We do tend to reinvent the wheel sometimes,” Baron says. “But, absolutely, [B.F.F.] existed decades before this.”

And, by the way, btw didn’t spring from chat, Twitter, or SMS. Nor did b/c for because or b/w for between. All are, Baron says, “way old.”

According to Carmen Fought, a linguistics professor at Pitzer College and the author of Language and Ethnicity, there is a chance that such common abbreviations could make their way into the language.

In that scenario, “the word because becomes ‘bec’ because people are used to [using b/c],” Fought says, adding, “I’ve had students tell me that they hear people saying L.O.L. aloud,” pronouncing the acronym for laugh out loud like the word loll.

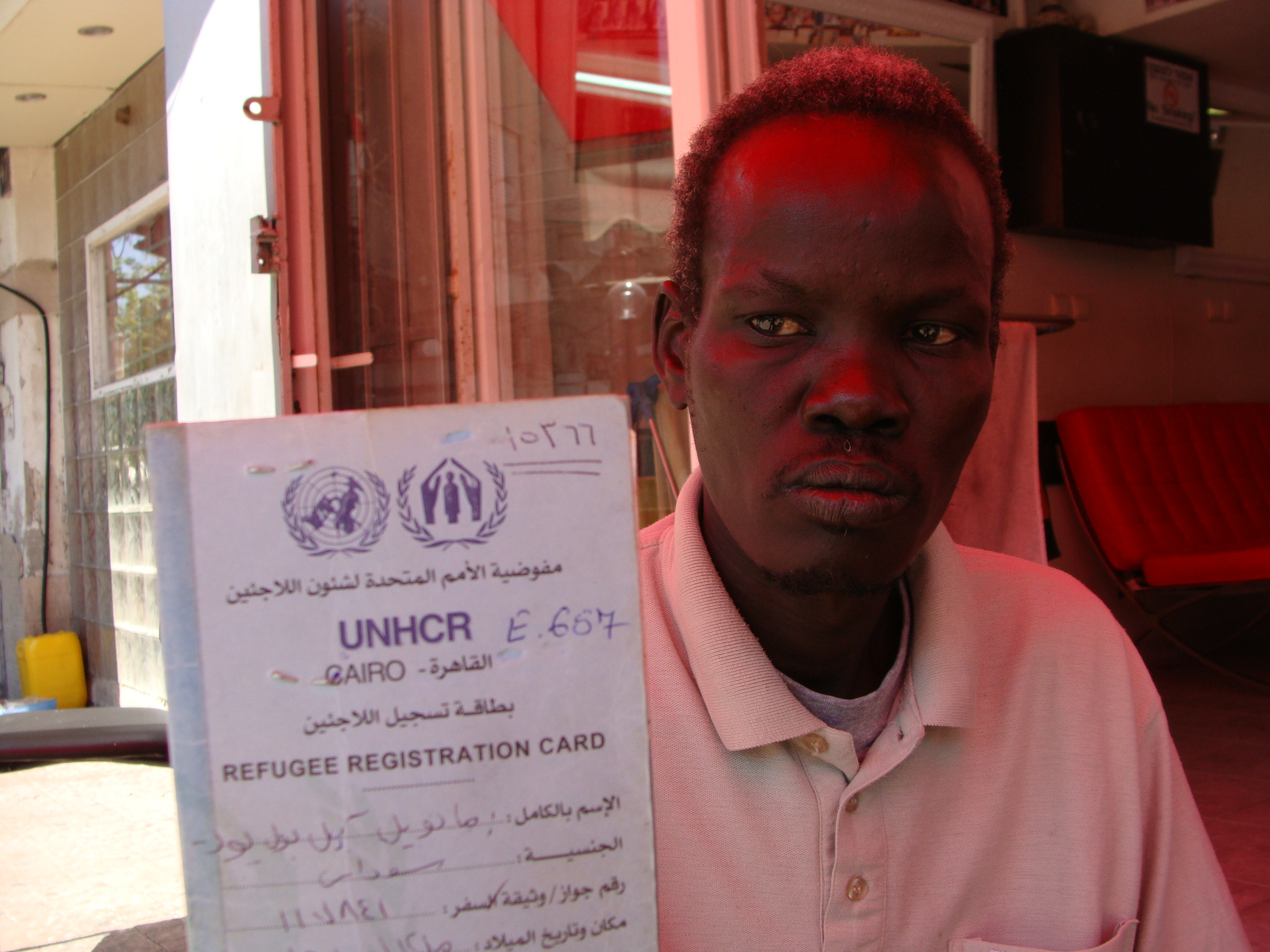

This phenomenon is common in the Philippines where abbreviations are embraced (a little too enthusiastically some say). For example, a Filipino who has grown up in America, or who has an American parent, is called a “Fil-am.” Overseas Filipino workers are referred to by their acronym: O.F.Ws. In my experience, saying “migrant workers” or “foreign workers” elicits weird looks and gentle corrections.

The national language of the Philippines, Tagalog, is a mixed bag. Although it’s a Malayo-Polynesian language, it has borrowed extensively from Spanish and English. Chinese immigrants also made a contribution to Tagalog; Sanskrit and Arabic have left fingerprints on the language, as well.

English is similarly open. Fought explains, “It’s like this mutt language, like the dog you pick up from the shelter that’s a little bit of this and that. “We’ve got Latin roots, Greek roots, French German, Scandinavian borrowings. English will borrow from any language.”

There are loan words from Hindi, Native American languages, and Spanish, to name a few.

“We’ll just take anything,” Fought says.

Which is exactly why we won’t end up taking the Hebrew system.

“There’s too much going on,” Fought remarks, offering the example of rbt. Is it rebate, a descendant of Old French? Or robot, on loan from Czech?

Because English is so chaotic, many English-speakers have a hard time learning to spell. And they seem to drift, naturally, towards what looks more like the Semitic system.

Baron explains, “What we do know about children learning to write English is that if they are allowed to spell however they wish… [they] leave out the vowels. In English, figuring out which vowel to put is tough. The consonants are generally much easier to figure out.”

But vowels are here to stay.

“Vowels are not our friends,” Baron says. “But, nonetheless, we have lived with them in English for a long time.”

Fought agrees. However, she adds, we could see the vowels fall out of languages that have simpler spelling systems. She muses, “It could work for Spanish where they only have five vowels.”