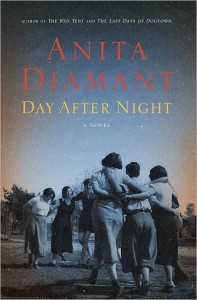

Review of Anita Diamant’s Day After Night

Review of Anita Diamant’s Day After Night

Haaretz, December 4, 2009

After the darkness of the Shoah, in the last days of the British Mandate, waves of Jewish immigrants flooded Palestine’s shores. Their numbers far exceeded the quotas set by the British, and these new arrivals — most coming by boat from Europe, a few traveling by foot from the Arab world, but all of them considered illegal — were rounded up and sent to detention centers in Palestine and Cyprus, where they waited for the British to decide their fates. One such internment camp, at Atlit, just south of Haifa, serves as the setting for Anita Diamant’s latest work of fiction, “Day After Night.”

Atlit, Diamant writes in the opening pages, “offered a grim welcome to the exhausted remnant of the Final Solution, who could barely see past its barbwire fences, three of them, in fact, concentric lines that scrawled a crabbed and painful hieroglyphic across the sky.” She draws on first-hand reporting for this description — a 2000 visit to Atlit, today a museum, gave her the idea for the novel.

Diamant is best known for “The Red Tent” (1997), which became an international bestseller. That book, in which the author took as her premise the biblical story of Jacob’s daughter Dinah, recasts Dinah’s woeful tale as one of feminine strength and triumph.

“Day After Night” centers on a historical event — the October 1945 rescue by the Palmach, the Haganah’s elite commando force, of over 200 illegal immigrants, 70 of whom were women, imprisoned at Atlit. Diamant focuses on a handful of vividly imagined, indomitable female characters, as she has in all of her other novels.

We meet the women of “Day After Night” in the prologue, while they sleep: “restless bodies rest, and faces aged by hunger, grief, and doubt relax to reveal the beauty and the pity of their youth.” All have yet to turn 21, and all immigrated to Palestine after losing their families in the Holocaust. The girls are traumatized, and their spirits are in a deep slumber.

The story, which spans three months in 1945, centers on four of them. Leonie, only 17, was forced into prostitution in Paris by a neighbor who threatened to expose her as a Jew to the Germans. Shayndel, an ardent Zionist, survived by taking to the woods and fighting alongside the Polish resistance. Tedi, a willowy Dutch girl with blonde hair and blue eyes, spent the war years hiding out in a barn. And then there’s Zorah, the most complex and compelling of the four. Zorah, who is from Poland, survived Auschwitz but remains imprisoned by her rage against God and life.

Of Tedi, Diamant writes, “Now all she could see was the fence: a million razor-sharp thorns telling her that she was still something less than free, something less than human.” Although EVENTUALLY??, the British usually let Jewish prisoners join the Yishuv in Palestine — setting “them free, like fish too small to fry” as Diamant puts it — the uncertainty of their futures and the fact that they still aren’t in control of their lives is terrifying to the girls. They have, in effect, left one prison, Europe, for another, Palestine.

“Day After Night” follows Zorah, Tedi and the others in the days leading up to the break-out and the night that they, at last, gain freedom. But this character-driven novel is about more than just escape. It’s about what happens to each woman emotionally in the long, slow days of waiting. Each woman confronts her past in order to forge ahead into the future.

Leonie passes her days by working in Atlit’s medical clinic, where she is trained by a Jewish nurse named Aliza. At Aliza’s side, Leonie also learns Hebrew and bits and pieces about Palestine.

Leonie’s healing process is disrupted when a German woman, Lotte, turns up at Atlit. Lotte is hysterical — cursing and screaming — and Leonie, the only one who speaks her language, quickly steps in to help. Leonie, like the other inmates, mistakes Lotte’s fear as a reaction to Atlit, whose appearance is reminiscent of a concentration camp. And it is rumored that Lotte had been imprisoned at Ravensbruck, a concentration camp notorious for the brutal medical experiments conducted on Jews.

But Leonie quickly realizes what Lotte’s true role in the Holocaust was when she glimpses a thunderbolt tattoo that signals her membership in the SS.

When the new arrival correctly guesses how Leonie learned German — tending to the sexual needs of officers of the Third Reich — she threatens to expose her to the other women in Atlit. “‘No one shaved your head and marched you out of town, naked, with the rest of the whores?’” Lotte hisses. “‘But maybe that’s what your friends here would do if I told them your secret.’”

Leonie must decide. She can preserve her integrity, or she can, shamefully, protect Lotte’s past and her own.

Shayndel, who has become Leonie’s closest friend since they met during the journey from Europe to Palestine, is revered for her heroism during the war. She is tapped by the Palmach to report on the movements of the camp’s British and Arab guards and to assist with a breakout. But Shayndel, for all her strength, has her own nightmares — she is burdened by survivor’s guilt, haunted by the memory of Wolfe and Malka, two fellow fighters she watched die in the forest. And as the operation approaches, Shayndel doubts her ability to lead another group of Jews in their break for freedom.

Tedi passes the time by throwing herself into learning Hebrew, chanting words to herself as she goes to the bathroom and washes her face. “She wondered,” the narrator tells us, “if she could fill her head with enough Hebrew to crowd out her native Dutch.”

Although Tedi also fantasizes about taking a Hebrew name, dreams of living “on a kibbutz where everyone smelled of oranges and milk” and admires the Zionists, she isn’t bound to ideology. She simply wants to forget. When a new group of survivors arrive in Atlit and pump the inmates for any knowledge they may have about missing loved ones from Europe, Tedi ignores the clamorous, emotional scene. Instead, she gazes toward the skyline and studies the mountains in the distance, attempting to repress memories of her own dead family.

Zorah, on the other hand, is so determined to remember that she compulsively fills one sheet of paper after another with lists that detail the suffering she witnessed at Auschwitz — the names of inmates, the labor they were forced to do, the deaths she witnessed, the scant meals the inmates had eaten. “Her registry of misery, humiliation, and loss covered five pieces of paper, front and back, a hedge against forgetting… She kept it folded within the pages of her Hebrew grammar, and ran her eyes over the columns every time she studied.”

The Jews of Palestine, busy with the work of building a new nation, enrage Zorah, as do the other survivors, who seem eager to bury the past. To Zorah, forgetting the dead kills them again; the idle chatter of the girls at Atlit sounds like “music at a funeral.”

At first, Zorah, riveted to the past, clashes with the forward-looking Tedi. But when Tedi’s memories burst the dam, it is Zorah who listens. In seeing a reflection of her own suffering, and by helping Tedi wade her way through it, Zorah begins to understand the need to look toward the horizon, toward Israel shining in the twilight of the British Mandate.

As one might expect, larger issues from the outside world intrude on the women’s attempts to find peace. There is one impassioned political debate, sparked by Arik, one of the camp’s Hebrew teachers. The British, according to Arik, are an enemy; the Arabs, he says, “want the Jews out — or dead.” The solution, Arik explains, is to drive out the former and fight the latter in order to secure a state for the Jewish people.

One of the students challenges him. “‘Maybe you can explain this to me, Arik. In all my years as a Zionist, in the youth groups and in all my reading, no one ever mentioned the Arabs. Now I come here to discover there are three times as many of them as there are Jews here in the land. Did any of you know that?'”

Arik replies that the Palestinians are “Worse than peasants. They are illiterate, dirty, backward. The educated ones with money use their tenants like serfs, like slaves. Besides, the Arabs did nothing with this land for hundreds of years. . .”

This debate, some might complain, is too short, and because there are too few discussions, the issues aren’t given the weight they arguably deserve. But Diamant had to make authorial decisions — and it seems that she made the right ones. Had she given us too heavy a dose of history and politics, she would have lost her characters in the wake. She manages to seamlessly integrate issues that continue to reverberate throughout Israel today: the religious and secular divide, the Arab-Israeli conflict, the tension between immigrants and native-born Israelis. Even the contrasts between Mizrahim and Ashkenazim get a little attention. But none of this comes at the expense of the women, who remain the true focus of the story.

With luminous, fluid prose, Diamant dips deep into the girls’ hidden wells of emotion and memory. When each woman rises from her nightmares, gasping as she awakens, the readers feel like they’re catching their own breath as well. For this novel is not just about women who have survived the Shoah — it’s a universally human tale about hope and healing.