The Nation, December 2, 2015

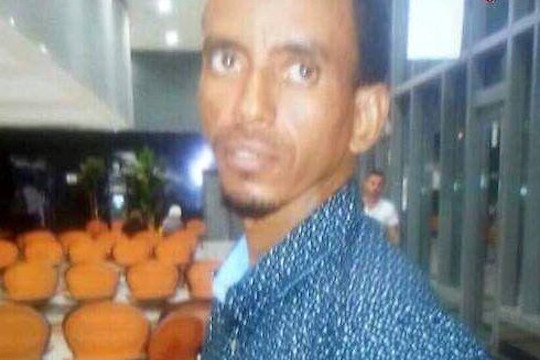

esfu Atsbha, 35, stands in the alley behind an unmarked Eritrean community center in south Tel Aviv, just blocks away from the park where a memorial service was held for Habtom Zerhum a few days before. Zerhum, an Eritrean asylum seeker, was killed when he was mistaken for a Palestinian terrorist during an attack on the Beer Sheva bus station. He was shot by an Israeli security guard, and as he lay bleeding on the ground, he was beaten by onlookers. One of them picked up a bench and dropped it on Zerhum’s head.

Atsbha is the chairperson of the Eritrean Solidarity Movement for National Salvation, one of the biggest diaspora-based opposition parties seeking to depose Eritrean dictator Isaias Afwerki. The group’s headquarters are in Ethiopia, where Atsbha lives. He landed in Israel in late October to find its community of 45,000 asylum seekers—most of whom are from Eritrea—in mourning and shock.

Not that things have ever been easy here. When African asylum seekers cross the border from Egypt to Israel, they are imprisoned. After they get out of jail, they are not allowed to work legally. So they take black-market jobs, where they are subject to exploitation. Israeli politicians and the mainstream media call them “infiltrators”—a loaded term that, for many Israelis, is associated with Palestinians. The Prevention of Infiltration Law, which Israel drafted in the early 1950s to stop Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes inside the newly created Jewish state, has been broadened so that the state can use it to detain African asylum seekers as well.

And for many years, the Israeli government refused to process their requests for refuge. Now officials take the paperwork and don’t reply. Or they summarily reject applications for asylum without thoroughly investigating claims, human-rights groups say.

It all stems from the state’s goal to “make their lives miserable”—the laws and policies are meant to deter African asylum seekers from coming, while pressuring those who are here already to leave. So far, it has worked. Several years ago, the community numbered 60,000. The South Sudanese who lived in Israel were deported in 2012; others who faced indefinite detention versus “voluntary deportation” chose to leave. Some who left Israel have tried to go on to Europe; a number drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. A handful were killed by ISIS.

Despite the immense pressure they face in Israel, many Eritreans were surprised by what happened to Zerhum, an event that the Israeli media called a “lynching.” During the interviews I conducted in the wake of his death, some told me that it pointed to how dire their situation is in Israel. Others remarked that it’s yet another tragic reminder of how urgent it is to stop the repression in Eritrea.

That’s why Atsbha’s here.

While he supports asylum seekers’ rights, he doesn’t believe that absorbing Eritreans and those fleeing other repressive regimes is a sustainable answer to Europe or Israel’s migrant crises.

“To accept thousands of refugees is not an easy task. It costs millions of dollars.… It’s not sustainable. The solution is to get rid of the system,” Atsbha says, referring to Afwerki and his regime.

A crowd of about 200 Eritrean asylum seekers, donning white jerseys emblazoned with the Eritrean Solidarity Movement for National Salvation logo, have gathered in the community center. Every chair is full. In the back, rows of men stand. They crowd around a pool table, the game they’d been playing moments before forgotten. All eyes are trained on Atsbha, whose story is not unlike their own.

Atsbha had only heard about prisons and torture in history class, when he’d studied the Ethiopian occupation of his homeland, Eritrea. But that changed in 2001, when he found himself detained without charge or trial.

Atsbha was a student at Asmara University then. He was in his final year, working toward a degree in public administration, when 20 people—11 high-ranking government officials and 10 journalists, a group that Eritreans call the G-15—disappeared.

Students, including Atsbha, started asking questions about the G-15, about “starting a democratic process, and [the] implementation of the constitution that was ratified in 1997,” he recalls. The head of the student council made a little too much noise and was arrested; Atsbha and others went to the courthouse in a show of solidarity. But justice was nowhere to be found—the group, which numbered in the hundreds, was rounded up and taken to jail.

Or something like it. They were held in an outdoor pen—300 people, Atsbha estimates, crammed into a 100 meter by 50 meter space. They were surrounded by a fence and armed guards. There was nowhere to bathe or go to the bathroom; the soldiers took them out once a day so that the prisoners could relieve themselves. Meals consisted of little more than bread and small amounts of water. There was no roof or shade of any kind, nothing to guard them from the searing heat.

Three of the students died from heat stroke while they were detained.

During the day, soldiers marched Atsbha and the other prisoners out of the pen to collect stones. Many Eritreans who have been detained or imprisoned speak of forced labor; other interviewees have told me that they were taken outside mid-day to dig ditches. Atsbha’s story is unusual in that he and the other students were held outdoors. Most Eritrean asylum seekers I’ve spoken to who have been detained describe dark underground prisons.

After 45 days, Atsbha was released. The experience, he believes, was meant to break any glimmerings of resistance. Instead, it planted the seed of revolution in his heart.

After Atsbha finished his degree, the government called him up to return to Sawa military camp, where he’d undergone three months’ basic training before university. From Sawa, Atsbha was sent to do civil service in the ministry of education. He received $10 a month for his work. Atsbha suspected that the government would never release him from duty—indeed, other Eritrean interviewees have been forced to spend a decade or more in the army, earning anywhere from $10 to $20 a month, with no end in sight.

Atsbha points out that keeping young men in the military indefinitely is another way to prevent the people from revolting.

Atsbha knew that if he went AWOL and was caught, he would be jailed. Still, he decided to flee. It was risky—many Eritreans have been killed by their own government as they’ve attempted to cross the border. So he left the country at night, crossing into Ethiopia in the dark in 2003.

He spent two years in a refugee camp there before joining his extended family, who had immigrated decades ago to Denver, Colorado. Atsbha arrived there in February of 2005, he recalls, and the streets were full of snow. He laughs as he remembers how shocked he was by the sudden change in both culture and climate.

But Atsbha adjusted to life in America. He began working part-time at a grocery store and studying medical technology. He got citizenship. He was comfortable, he says, but he couldn’t sleep at night.

“I never forgot about my land. Every day we heard bad news: people are dying, people are arrested, people are going out [emigrating].”

By this time, Eritreans were already making the trip to Libya, where smugglers ferried them across the Mediterranean to Italy. They began to arrive in Israel in 2006; some interviewees have told me that they went to Israel after they’d waited for months in Libya, only to give up on getting to Europe.

“What will be the future of the country [if everyone leaves]?” Atsbha asks. “We, as a people, will have a very ominous future.”

He worried about the fate of his parents and six siblings, who remain in Eritrea. He also thought about his “ancestors,” he says. “I have the land where I was born that I was given by God.”

In 2012, Atsbha decided to return to Africa. Because it was too dangerous for him to enter Eritrea, he went to Ethiopia. There, he got involved in the Eritrean Youth Solidarity for National Salvation, which was founded in the same year; it later changed its name to the Eritrean Solidarity Movement for National Salvation in order to broaden its appeal.

Today, the movement is trying to strengthen its network between those in Ethiopia and other nearby countries and “clandestine organizations” in Eritrea. But Atsbha admits that it’s impossible to overthrow the regime from the inside at this point. So the first step, he argues, is to get the Eritrean diaspora organized.

It’s no short order. Since they began to leave the country in large numbers around 2000, Eritreans have fanned out across the globe. Various opposition movements have sprung up; Atsbha puts the number at 17. These groups must be unified, he says, under a clear goal—a lesson they could learn, perhaps, from the Palestinian struggle, which does not have one crystallized aim and is plagued by internal conflicts.

The organization also aims to raise awareness about Eritreans’ plight through various nonviolent means, including seminars, workshops, and demonstrations; they hope that this will cause the international community to put diplomatic and political pressure on Afwerki to step down.

Ultimately, resources from the diaspora must be pooled so that the opposition movements can “gain…the necessary equipment for the revolution,” Atsbha says. “The sharpest…edge of any struggle is armed struggle.”

“But that’s not our choice,” he’s quick to add. “That’s a final resort.”

In some respects, the group’s efforts are reminiscent of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s in its early days. And just as the Palestinian struggle was—and continues to be—often misunderstood, so is the situation in Eritrea.

“Right now, the international community doesn’t recognize the exact cause [of people’s leaving Eritrea]. Some of them, they see it as an economic case…. others say it’s the endless military conscription,” Atsbha reflects. “What makes them leave the country in such numbers and risk their life? It’s a question of liberty. It’s a question of political rights.”