Los Angeles Review of Books, January 20, 2013

On the last day of the semester at Al-Quds University in the West Bank, I entered the classroom to find the usual graffiti on the whiteboard, save for an odd symbol. It was a triangle filled with curlicues, topped by two circles with dots in the middle. I talked to my students — all freshmen in college, mostly women, most in hijab — as I erased the board but found that the symbol wasn’t going anywhere. So I kept rubbing. A few of my students began to giggle. The harder I rubbed, the harder they laughed.

I stepped away from the board and looked at the triangle and circles. It snapped into focus: a patch of pubic hair topped by a pair of breasts.

“Oh,” I said, glad my students couldn’t see my face. I was embarrassed that I’d rubbed a picture of genitalia in front of “my kids,” as I call them.

But I was more embarrassed that I’d lacked the imagination to see what was right in front of my eyes, that I hadn’t expected to find a universal sign of sexuality here (what is more timeless than a woman’s organs?), that I had seen my students merely as “Muslims” and that I somehow, in my mind, had precluded their normal, human desires and the conflicts that come with them.

*

Fida J. Adely similarly calls the reader to task in Gendered Paradoxes: Educating Jordanian Woman in Nation, Faith, and Progress. I’m not usually one to quibble about titles but, in this case, the dry title does a major disservice to this energetic, highly readable exploration of identity politics in a young nation. What’s more, the title also implies that Adely will uphold Orientalist tropes by invoking the prevailing Western view of Jordanian women: that their low workforce participation and high fertility rates despite increasing education suggests a “paradox.”

Rather, Adely allows high school–aged girls to speak for themselves. She uses their stories to examine the larger issues of why Jordanian women often pursue degrees but not careers; how the young women negotiate their relationship with Islam; and how the educational system helps solidify a national identity while simultaneously serving as a place to discuss Islam.

The latter is, perhaps, the true paradox of the book. While the monarchy co-opts moderate Islam for purposes of state-building, more conservative forms of the religion present a challenge to the king’s authority and the primacy of the nation in citizen’s lives. This is particularly relevant in Jordan today, where the Islamic Action Front (the Jordanian arm of the Muslim Brotherhood) is leading weekly protests in the capital city of Amman that, some observers say, could boil over and topple the monarchy.

Jordan, like Egypt, is troubled by high unemployment: while official numbers put it at 13 percent, unofficial estimates say the jobless rate is a whopping 30 percent. When a Jordanian does manage to find work, his wages are low. Cost of living is unmanageably high and rising.

On my last reporting trip to Amman, Jordanians told me that college degrees weren’t helping them find jobs. Many were also concerned about the fact that the economic situation is forcing Jordanians to marry later. As men are expected to provide financially for their wives, a man doesn’t marry until he’s able to do so.

One woman I interviewed at a Friday protest said that she had to give her 26-year-old son — who holds a bachelor’s degree in graphic design but was unemployed — the money to start a family of his own. A shar’ia (Islamic law) teacher of Palestinian origin, she was protesting not against the monarchy but the state of the state. King Abdullah II continues to promise reforms but has been slow to deliver.

Women’s rights are a concern, as well, and have been the subject of a few small protests since Jordanians first began demonstrating almost two years ago. Jordanian women are unable to pass their citizenship on to their children and groups have gathered in the capital city to demand reform. Teachers, many of whom are women, have held massive strikes against stagnant wages, shutting down the state school system for weeks on end.

*

Though Jordanians were not yet protesting when Adely did her field research at an all-girls high school in Bawadi al-Nassem, a small town just 40 miles from Amman, the issues that have given rise to demonstrations were already simmering. It is against this backdrop of political and economic uncertainty that Jordanian girls go to high school and look to their futures. With limited job prospects, some young women see education as a means of “marrying up,” Adely explains; Jordanian men looking for a bride eye educated women because they can make an economic contribution to the household.

Anwar, a tenth grader, explains, “The potential groom […] the first thing he asks is: ‘How much is her salary?’ He wants her to help him.”

Adely reminds Anwar that most Jordanian women stop working after they marry and asks, “So what is the benefit from the salary in the end?”

Anwar answers, “A woman who is an engineer won’t marry a laborer. People will typically come and request the hand of someone of the same class.”

Going to school, Adely explains, is also a way for a young, unmarried Jordanian woman to advertise her availability. It makes “a girl who might otherwise spend most of her time at home more visible, even if it delayed marriage.” While premarital romances are frowned upon and, as Palestinian students tell me, can “ruin” a girl’s reputation for life — dashing her chances to marry — Adely found that Jordanian parents sometimes allow their school-age daughters “to be strategic about increasing their ‘prospects’ […] This meant that some adults might look the other way if a relationship was budding or intercede to ensure that it remained ‘honorable’ and resulted in marriage.”

Though education is often a means of “catching” a good groom — either by making eyes at men on their way to school or by getting the college degree that will attract a quality suitor — Adely explains that some Jordanian women do the opposite. They find husbands that will help them pursue a degree. For many Jordanian girls and their parents, education serves as a safety net in case a woman doesn’t find a partner, or ends up divorced or widowed.

I found that the same holds true in the West Bank. Noor is an 18-year-old university student who is engaged to an older, established cousin. So why bother get an education? She tells me, “My parents were like, ‘La samah allah [God forbid] your husband dies or something, you have that degree and you can go out and work and not beg for money.’”

And then there are those women who don’t see education as a status symbol or an insurance policy. They simply use their degrees to work.

Dr. Sumaya is a wife, a mother, and a physician who, Adely explains, is “considered a trailblazer for women” in her Jordanian village. So it’s a bit surprising to find that Dr. Sumaya “seemed uncomfortable” with Adely’s “interest in her story.” Speaking to Adely, the working mother confesses that she regrets having studied medicine.

I feel bad for my kids. I don’t have enough time for them. What adds to this is that my husband is also a doctor who travels, and so he is not even here during the week […] Our financial situation is quite good because my husband and I both work, but our work is very demanding. It’s difficult.

But young women are equally conflicted about their paths. Anwar tells Adely, “You ask a girl why she is studying and she says because she wants to go to the university. Then she wants a groom […]”

Lena, the daughter of a teacher, chimes in, “Also, now there are a lot of women who work, and they see the women who do not work living a life of luxury — not tired. They start thinking about retiring or quitting […]”

She goes on to explain that her mother eventually left her job because she always came “home worn and tired. When she would see the women sitting at home, she would feel as if something were missing from her life.”

*

Adely emphasizes that her interviewees don’t represent Arab women in general; the high school girls only speak for themselves and their individual experiences. This type of disclaimer is a must for someone like Adely, an academic writing against the Western gaze and the many stereotypes that come with it. But the girls’ experiences do, of course, reflect the circumstances and society in which they live.

Amman offers a particularly dramatic example of the pressures Jordanian women are under. As is the case in many societies, city girls here are considered “freer” than those who live in villages. But Sandra Hiari, an architect and urban planner, points out that it’s uncommon to see Ammani women on the street alone.

While a growing number of Jordanians families — even low-income ones — are buying cars, usually it’s the husband who takes the car to work, leaving the woman stranded at home. When a woman dares to take a bus, she faces sexual harassment. So women are confined to taxis — an expensive proposition in a poor country — and this restricts their movement. One survey found that women’s transportation issues are partly to blame for their low rate of participation in the work force.

When I reported on Amman’s urban planning and its impact on women’s lives, Hiari told me,

“I think we women are captured in bubbles. We move from one bubble to another in the city.”

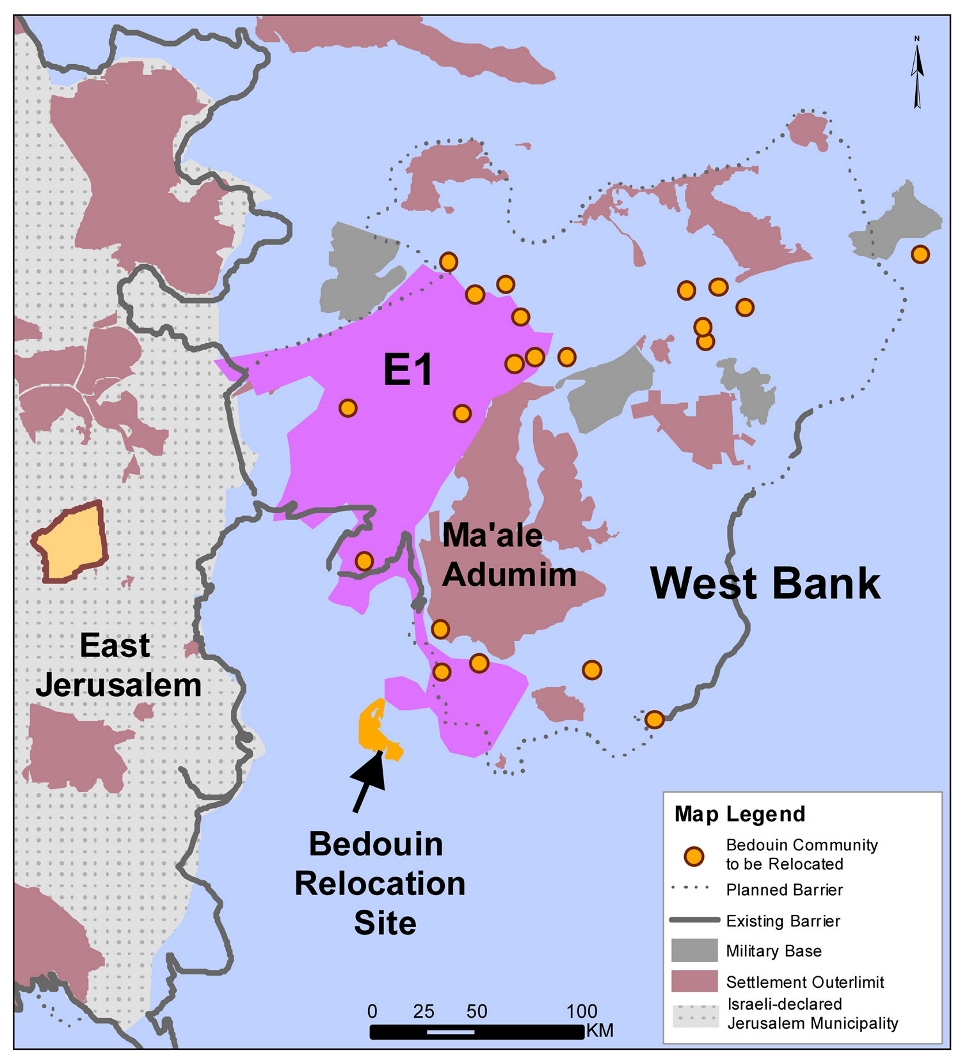

Young Palestinian women also find their mobility limited. But it’s not because of poor urban planning. Israel’s occupation restricts Palestinian freedom of movement.

Noor said, “The occupation makes education harder. Actually from the university it should be like 30 minutes to my balad not two hours. But [because of Israeli checkpoints and the separation barrier] you have to go around.”

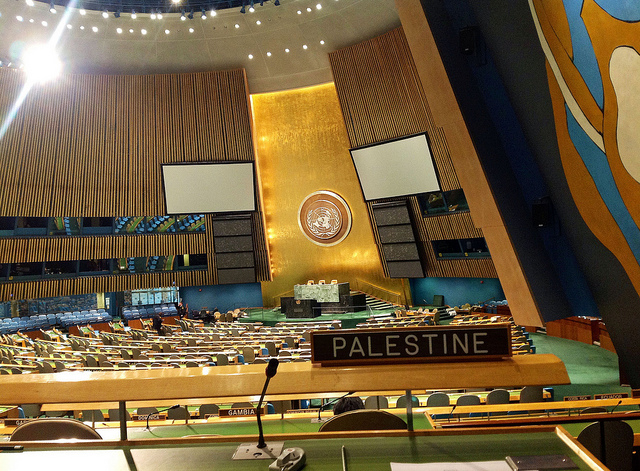

Under such circumstances, going to school takes on an additional layer. It becomes an act of resistance against the Israeli occupation. It’s something a girl can do for Palestine.

Nawal, an 18-year-old studying English literature, remarked, “[T]he more you learn, the more you can help Palestine economically, politically, socially. I mean, you have people who are learning urban studies. They can help us with planning. We have lawyers that can help us.”

Noor continued, “We also have research facilities that can lead to discoveries and along the way people from Palestine will get recognized that they discovered [something] and not that we [made] the world’s biggest knafeh [cheese dessert] […] Because, seriously, we’re known for that kind of stuff.”

Even though the girls laughed, some Palestinians argue that food has a place in state-building. Whether it’s a Palestinian chef abroad, a bottle of olive oil stamped with the words “Made in Palestine,” or Taybeh beer, the Westerner who associates Palestine with violence or terrorism is exposed to something that changes their idea of the occupied territory and the people who live in it. The same could be said for scientists and scholars.

“We can’t go against Israel because they have such a strong military,” Salma added, “but if we educate ourselves we will be able to come up with some sort of clever strategy to liberate Palestine.”

Salma is from a conservative Muslim family. Although they now live in the West Bank, they are refugees from a Palestinian village that was destroyed during the 1947¬–1948 war that surrounded the establishment of Israel. Just as Jordanian women are conflicted about their educations, Salma offered me several contradictory answers when I asked her what she hopes to do with her degree.

“I’m studying media because I want to be a journalist […] I don’t want to stay at home after four years of studying,” she answered.

Just a few minutes later, Salma said, “I think the most important thing after we finish college is to marry […] In our society there is a saying: ilmarra labeitha [A woman is for her house].”

But at the end of our roundtable discussion — which included three other 18-year-old Palestinian women who attend a university in the West Bank — Salma confessed that, when she thinks about the future, she is worried about finding a job. Because of the tough economic circumstances of the West Bank and Gaza, many young Palestinian women, even those who believe that a woman is indeed for her home, share this concern.

Amira, an 18-year-old who is majoring in journalism, explained, “Guys now — most of them are trying to find girls who want to work because life now is hard so they want someone who will share —”

“The financial [burden],” Salma finished.

“Yeah, this is what I see right now,” Amira continued. “But before, they like —”

It’s a story the girls know well. Noor finished Amira’s sentence as Salma did. “[Some Palestinian men] didn’t want to educate women because they thought it would lead to a rebellion in the house.”

*

When it came to issues of gender, throughout my conversation with the Palestinian girls I was struck by the same feeling I had as I read Adely’s book: that there is nothing particularly “Arab” about their experiences. Growing up in the Deep South, I’d seen “easy” girls ostracized. I, too, had a mother (albeit a “Western” one) warn me that she would kick me out of the house if I dared to have a baby out of wedlock. Didn’t Mom tell me that I’d better be careful about how I interacted with boys because no one would “buy the cow” when they could “get the milk for free?” Later, in university, hadn’t I met girls who were there just to catch a husband? How often do we see engineers and laborers marry each other in the United States? Hadn’t I known young women in the United States who used education to marry up, whose law and master’s degrees are now collecting dust? Hadn’t my former mother-in-law lectured me that women can’t have it all, that we still have to decide between a career and a family?

Why do Americans consider my Baptist friend in Florida who dresses modestly “conservative,” while a woman in a hijab is thought to be “oppressed” or “extreme”? Note to Western women: just because your society or culture encourages you to show some skin doesn’t mean you’re freer than the women who are pushed into covering theirs. What is the difference between my ex-husband, who wanted me to dress like a tart, versus the man who wants his wife to hide in a sack? It’s two sides of the same coin: either way, the female body is sexed and serves as a site of dis/honor.

As Adely points out, an educated American woman who chooses to stay at home with her children is often applauded for exercising her right to choose while Jordanian women who make the same decision indicate, to Western observers, a lack of development in the “Arab world.” Meanwhile, in the West, the gap between men’s and women’s wages persist. Isn’t the phrase “pink collar” still being tossed around? Young Palestinian women are just as worried about earning a decent living without being confined to certain professions. As Nawal told me, “[T]he only places you’ll find [women working] is, like, teachers in schools and things like that. You know, you can’t find a woman head of state in Palestine […]”

While Gendered Paradoxes offers a revealing look at the lives of Jordanian girls and women, it also forces us “Western” women to hold the mirror up to ourselves. The book serves as a reminder that the so-called culture clash between the “Occident” and “Orient” is less about meaningful differences and more about the constructs that prevent us from acknowledging our similarities. It’s the West’s best defense mechanism: by pointing our collective finger at the East’s so-called lack of progress we can avoid confronting our own troubled relationship with gender.