IRIN, November 23, 2015

Faten Ghosheh, a 33-year-old Palestinian mother of five, stands on the roof of her partially demolished home in Jerusalem’s Old City, the Al-Aqsa Mosque visible behind her.

She recalls the moment five years ago when Israeli forces arrived at 5am to tear down the two rooms and bathroom that her husband had built with their life savings of 700,000 shekels ($180,000).

To avoid the fine that the Jerusalem municipality would charge for the demolition, the Ghoshehs called on the men in their family to come and tear down the walls.

“The children were all crying,” she says. “The older children brought hammers and started demolishing with their father.”

Now the family of nine, which includes Ghosheh’s sister-in-law and mother-in-law, makes do with only one bedroom.

“In order to protect this, the mosque,” she explains, gesturing towards the glistening dome on the horizon, “we will continue to live here. We consider ourselves … defenders of Al-Aqsa.”

Her comment explains at least some of the sentiment behind the wave of violence in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories that began last month and has claimed the lives of 16 Israelis, an American, an Eritrean and at least 90 Palestinians, including attackers.

For many Palestinians, Al-Aqsa, which stands on land Israel occupied in 1967, is as much of a political symbol as it is a religious one.

Alleged Israeli provocation at Al-Aqsa and the Temple Mount – holy to both Jews and Muslims – were a match to the powder keg of home demolitions, taxation without services, classroom shortages, and grinding poverty.

As much of the violence has shifted to the West Bank (although there was a stabbing Monday in West Jerusalem) East Jerusalem remains a focal point for protests, and the issues Palestinians face there are on full display inside the walls of the Old City, where the flare-up began.

Building permit woes

The Ghoshehs applied for but were denied a building permit for the rooms that were eventually torn down. Human rights organisations, including the Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI), argue that it is nearly impossible for Palestinians to get permits.

Only 14 percent of Palestinian East Jerusalem is zoned for residential use; less than eight percent of Jerusalem’s total landmass for a third of its population.

In 2014, Israeli forces destroyed 98 Palestinian structures in East Jerusalem because they were built without permits. Two were in the Old City, displacing seven people, including five children.

The Jerusalem municipality insists Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem can obtain building permits. The city points to 2014’s numbers: 108 permits were requested for East Jerusalem; 85 were granted.

Asked if these permits were granted to Palestinian residents or the Jewish Israeli settlers who live in East Jerusalem, Ben Avrahami, a spokesman for the municipality, said he did not have that information on hand.

The reality is that many Palestinians feel ahead of time that they will not be granted permits. By ACRI’s count, an estimated 39 percent of the houses in East Jerusalem have been built without permission.

“It’s not because we want to make their lives more difficult,” Avrahimi told IRIN. “It’s a problem with tabo [land registration]. It’s very complicated to prove ownership.” To that end, he adds, the city has started a special committee to examine those who claim ownership but lack all of the documentation, though not in all of East Jerusalem.

Lack of services

After the demolition, with the roof of the top floor torn away and most of the walls gone, the Ghoshehs added tin in an attempt to keep out the wind and rain. But it isn’t enough. During heavy winter storms, water leaks into the home. The city has fined them for the erecting the tin.

The family also pays arnona, property tax, to the municipality. Paying it is crucial to East Jerusalemites as it helps them prove that the city remains at the center of their life – a condition they must meet to hold on to their residency and, thus, Israeli IDs. According to the UN emergency coordination body OCHA, more than 14,000 Palestinians have lost their Jerusalem residency since 1967.

When asked what services she receives in return for the tax, Ghosheh remarks: “What services?”

Jihad Yusef agrees. The 49-year-old has brought her six children up in the Old City, and was born and raised inside its walls.

She recalls her attempt to enroll her son Ibrahim in the government-run school near their home. There was no space, so she had to put him in a private school that cost her 3,000 shekels ($770) a year.

OCHA estimates the city needs to supply an additional 2,200 classrooms to meet the Palestinian community’s educational needs. The municipality argues it is tackling this issue, telling IRIN in an emailed statement: “We build 100 new classrooms in East Jerusalem every year, more than any other sector in Jerusalem.”

Other basic services are also lacking. Palestinians from East Jerusalem are entitled to Israel’s public healthcare system, but there is only one clinic that provides free prenatal, infant and pediatric services in the Old City, and it’s in the Jewish Quarter. Likewise, East Jerusalem has seven of these clinics and there are 26 in the city’s Jewish neighborhoods, three of which also serve Palestinian families.

The Arab areas – that is, the Muslim, Christian, and Armenian Quarters – have a higher population density and many of the buildings there are in poor condition. As of 2002, according to a UN report, a third of Palestinian houses in the Old City lacked running water and some 40 percent were not connected to the sewage system.

Hard times

Ghosheh’s building is just a short walk from Al Wad Street – the narrow, cobblestone thoroughfare that leads to Al-Aqsa, Islam’s third holiest site, as well as the Western Wall, which is sacred to Jews and where the first stabbing attack took place in October.

Nabil Abu Sneineh and his brother, Saadeh, own a bakery on this road. They estimate that sales have dropped 90 percent since the flare-up began.

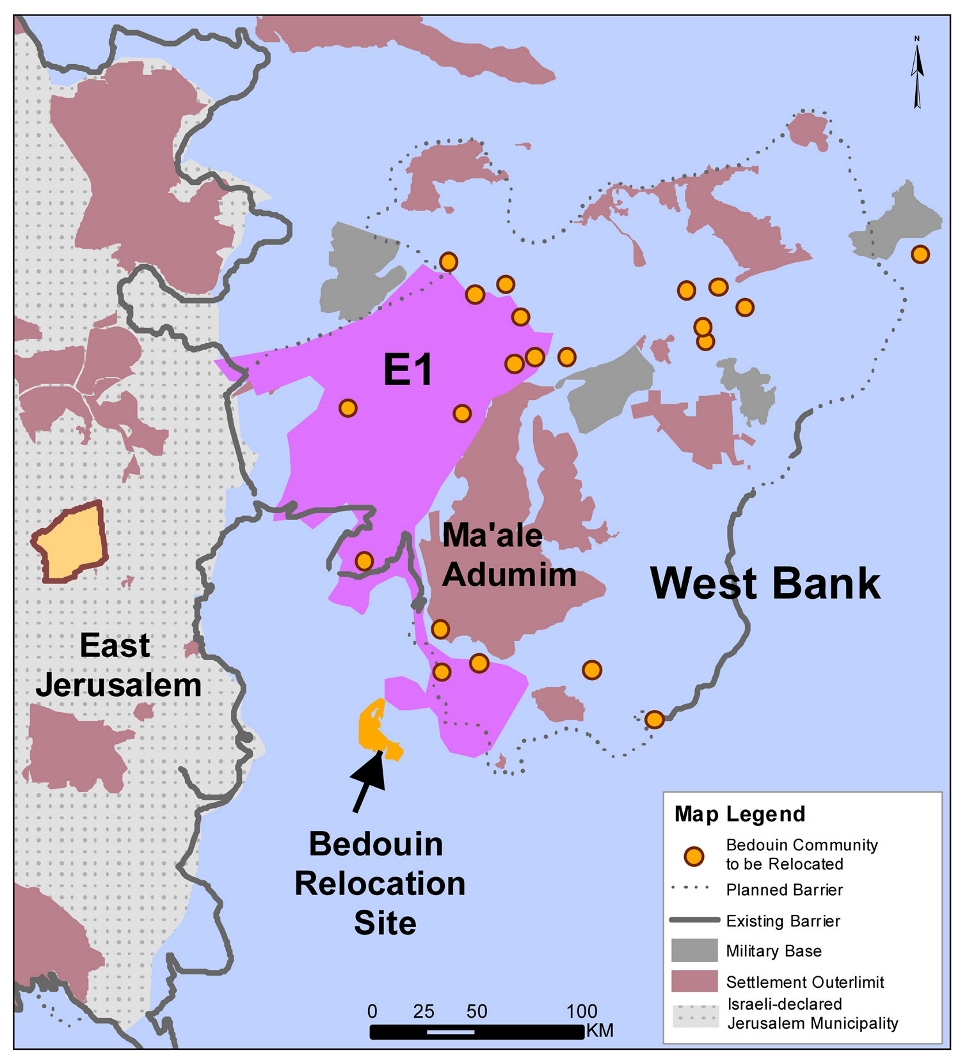

Historically, the area has been a centre for Palestinian trade. But West Bank suppliers have trouble reaching their traditional markets and vendors, thanks to the difficulty in acquiring Israeli government-issued permission to enter and navigating checkpoints, especially since the construction of the separation barrier that divides Israel from the West Bank and cuts through part of East Jerusalem. Many of the buyers who used to come to the Old City to do their shopping are now absent.

ACRI estimates that since the separation barrier’s completion, the percentage of those who live in East Jerusalem neighborhoods outside the barrier and do their shopping in Jerusalem has dropped from 18 to four percent. “Businesses in the centre of East Jerusalem and in the Old City have been particularly hard hit, and layoffs have become more and more frequent,” the association says.

The unemployment rate for Palestinian men in East Jerusalem hovers around 40 percent. In the Old City, some estimates are as high as 50 percent.

“[Israeli forces] close the streets any time they wish,” Saadeh Abu Sneineh, 32, says. “They harass us as we’re walking into our shops. Many [Palestinian men] have been strip-searched as we’re walking into the Old City.”

With sales so sluggish now, the Abu Sneinehs are worried they won’t be able to pay the property taxes on the business, which could result, eventually, in losing the bakery.

Ziyad Hammouri, director and a founder of the Jerusalem Centre for Social and Economic Rights, which offers legal aid to East Jerusalem Palestinians, says the most common problems are home demolitions, inability to pay property tax, and revocation of residency. Three houses were demolished in the city the day before he spoke to IRIN.

The municipality has always sued Jerusalemites who fell behind on their tax payments, going as far as seizing cars, bank accounts, and wages. But this phenomenon hits Palestinian residents harder as they are, by and large, poorer than their Jewish counterparts and are more likely to fall behind on arnona in the first place.

Hammouri is particularly concerned by recent attempts by the city to seize and auction off Palestinian property to pay off arnona debt.

“[The Israelis] want a political result from this economic oppression,” said Hammouri. “The goal is to push the people outside the city [beyond the separation barrier]. But first outside the Old City.”

However, the family of nine Ghoshehs is going nowhere in a hurry. Faten says she remains determined to stay in the house her husband’s family has owned for decades, although she admits wearily: “Living in the Old City is like suffocating.”